04 July 2024

“Let go of all your images of James Bonds, generals, politicians, kings, or queens” – Bart Oor talks about his path from an engineer to a leader

Are you one of those engineers who quietly believe they could make a good leader? Hiber’s Director of Engineering Bart Oor thinks you should be quiet no more! However, don’t consider this a free pass for whining or hostility. By sharing his path to leadership, Bart tells us how he learned to speak up constructively, believe in other people, and find more meaning in his work.

The CTO vs Status Quo series studies how CTOs challenge the current state of affairs at their company to push it toward a new height … or to save it from doom.

If you want to be a technical leader, you have things to learn… and unlearn

So, you want to become a technical leader? Let’s start with some bad news. No, it’s not your destiny, and no, you’re not going to save the company all by yourself and then get half of the kingdom.

According to Bart, leaders like this belong in the realm of fiction. You need to get rid of those images if you want to succeed. And that’s just one of many misconceptions and bad habits to eliminate.

But there is some good news, too. Ultimately, you don’t need to slay a dragon or reinvent the wheel to strive for leadership positions. It’s all about:

- Being passionate – when you do what you love and go the extra mile, people will find you dependable and flock to you.

- Being ready to speak up – when you share opinions openly, even if you are young, you change how people think of you. You don’t need the leader label to do that!

- Believing in others – when you are opinionated in a respectful way of others, you create a collaborative environment, which is what being a leader is about.

Read the interview to get practical examples, tips, and frameworks that will allow you to shape such a mindset.

Bio

A solution-oriented technical leader with over 10 years of experience. Bart began his career as a mechanical engineer and gradually transitioned into a managerial role. Today, he is the Director of Engineering for Hiber. He is responsible for facilitating expansion projects of Hiber’s well-monitoring solutions.

Expertise

Team management, project management, business development, product development, coaching

Hiber

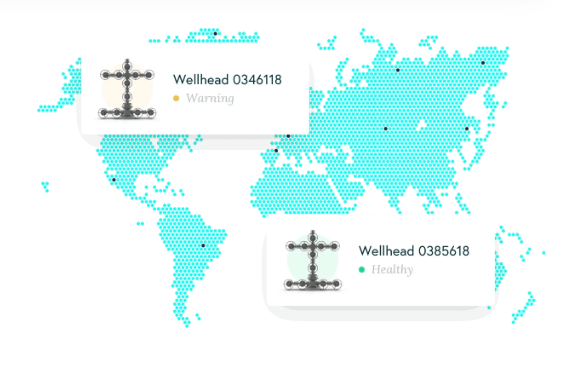

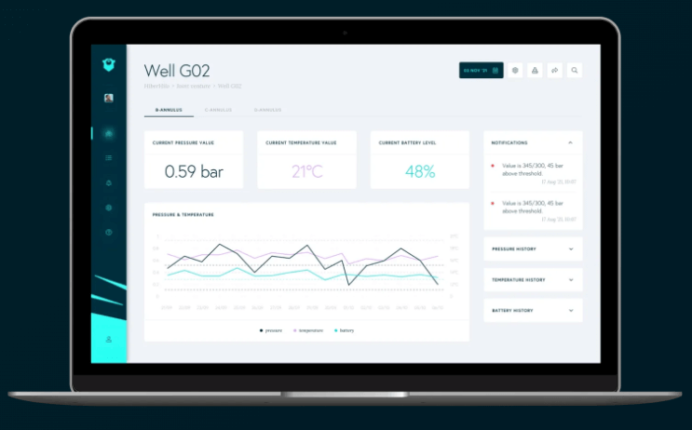

Hiber combines the power of the Internet of Things and data to offer an all-in-one remote monitoring solution for the energy industry. With Hiber’s software and hardware, companies can get frequent satellite-powered status updates for their remote wells, regardless of how far they are located.

Hiber’s vision

Arek Kowalski: Hello Bart. Thanks for taking the time to do the interview. After all, you must be pretty busy these days. Your well-monitoring solution for the energy industry, HiberHilo, is getting traction with companies as big as Shell. The solution is now available in the US, Brazil, and Nigeria.

What are you up to at Hiber today?

Bart: We provide instant well-monitoring solutions to the most remote areas, including mountains and deserts.

There are many oil and gas wells around the world. Typically, they are not installed in busy or populated places. Many of them are about as far from them as it gets. We have a satellite-based communication system designed so that you can get status monitoring automatically every five minutes instead of going there by helicopter every few months.

To that end, we provide everything – from software with easy-to-use dashboards to hardware – and sell it as a subscription. As you said, we’re successfully expanding to more countries. In addition to those you mentioned, we’re now in Mexico, Gabon, Papua New Guinea, and Romania, among others.

From an engineer to a leader – Bart’s story

As exciting as Hiber’s story is, I want to talk to you about your story. I want this interview to be a helpful resource for engineers who want to become leaders, and that’s exactly what you did during your 10+ years in the business.

Let’s move all the way back to the time before you entered the industry. When you graduated from mechanical engineering in Arnhem in 2011, did you think about becoming a tech leader in the future?

To be honest, I didn’t. I’ve always been interested in many things beyond technology. But at the same time, I always thought of myself as a mechanical engineer.

The thing about being an expert is that you will mostly be asked to share your expertise in the field you’re known for. The chances of doing something else are a bit limited. When you’re a tech expert, hardly anyone comes to you to ask for a creative solution in marketing, sales, HR, etc. That made me feel restricted.

When I began my career in the bicycle industry, I realized at some point that there may be more I can do. Gradually, I moved from an expert role into a lead engineer and team leader role.

Tell me more about this four-year transition from Product and Lead Engineer to managerial role. What skills did you acquire that would later help you hit your stride as a manager?

I was never scared to speak up, even if it was mostly about technical matters. When I felt sure about my view, the calculations, or the drawings I did, I always made it clear. It was also about that time that I noticed that people really listen to you if you know what you’re talking about.

I was quite young then. I was 21 on a mechanical engineering team that mostly consisted of people who were 40-50. They had a lot of experience; I was in training. But at the same time, I felt there were subjects I knew a lot about. I could follow what my more experienced teammates said and form my opinion.

So, my first big advice to anyone wanting to be a leader someday is to speak up. You don’t have to be an extrovert to do that, but stop telling yourself that people don’t listen. It’s good to push a little bit further and see what happens. You will gain respect when you listen carefully and make your own argument, providing the right background, even when you are young and lack experience.

Sometimes, it’s easier said than done. Is there some method you know that can help someone step out of their comfort zone and be more confident about speaking up?

One way to do it is to start your argument with a question rather than a direct opinion.

I’d begin a conversation with: “Have you considered this or that?”. If you bring up an opinion, people may say: “You’re pushing me away. You don’t listen to me”. But if you start with: “That’s an interesting design. Why did you do it that way? Why is it on the left side rather than on the right side? How did you take care of it?”, they will thank you for your input.

Your teammates will likely not get defensive when confronted with a question like this. Chances are you will change their mind. But it also takes a lot of pressure off of you. People are often afraid of being wrong. But if you start with a question, you cannot be wrong.

We’re now at the end of the engineering stage of your career.

You said earlier that the need to step out of your niche pushed you onto the managerial path. Was it just that? Experienced engineers sometimes choose between a managerial path and a more technical one. Once they do that, they typically stay on that path for years to come. Going back is very difficult. They are at a crossroads, so to speak. Tell me about this choice of yours.

The truth is that sometimes there’s simply no reason. Things just happen, and you can’t push them.

At some point, I participated in a very interesting project. I wanted to be part of it. When you feel a passion for something, you are extremely motivated to bring it to a good end.

By the end of the project’s first week, it was clear that I had made a good impression. I was driven, ready to go to the other side of the world if need be, stay a bit longer, and go the extra mile. As a result, I was eventually offered the lead engineer position for the project.

In this new capacity, I was asked to facilitate and organize instead of doing everything alone. This was a very new skill set for me. I had to learn how to make better use of the people around me and their skills to the benefit of the project. I also had to drop my own ego and accept other people’s better views or solutions.

What were your biggest challenges in this new role? I know that some new managers struggle to delegate tasks and eliminate the habit of micromanaging. Our series often discusses the importance of self-managed and cross-functional teams. Did you always like the idea, or was it a process for you to learn this skill?

I made some terrible mistakes in the beginning.

The first thing I did was start checking teammates’ output and making small corrections in processes or documents I didn’t like. Soon, I noticed that it was not sustainable or scalable. It’s really quite naive to think that you’re more knowledgeable than everyone else on a team. There’s only so much time you have. You can’t be the best in everything

So I eventually said to myself, “Let’s assume for a minute that they know what they’re doing. Let’s invite them to an open debate if they’re in doubt. Then we’ll see what will happen.”

I’ve also been on the opposite end of the spectrum. I took quite an extreme path of letting go completely. Before, I did the work by myself and controlled everything. Now, I gave my teammates complete freedom and didn’t control almost anything. I tried this approach for a month. When the time passed, I realized I didn’t know what they were doing anymore.

Micromanaging and letting go completely are two extremes, two sides of the same coin. Typically, these two approaches don’t work. You want to stay somewhere between these extremes. But finding the exact sweet spot is difficult. It depends on a specific team, person, project, and yourself.

I imagine it gets even more difficult when the size of your team grows. Three years later, you became a System Architect and indirectly managed even more people.

At that point, I was the engineering manager for a team of 15-18. I was also the hierarchical manager, conducting job interviews, salary reviews, etc.

Eventually, I found a balance between being an expert and helping others use their expertise.

However, I noticed that I was maintaining an already existing and functioning system. It matured after several yearly product development cycles and no longer required radical changes. My contribution was reduced to making small corrections after someone left. It didn’t make me happy.

Many of our guests also said that at some point, as you climb the managerial ladder, you no longer have any time to code, which made them feel like they were missing out. Was it the same for you?

I wasn’t doing engineering when I took on the team manager role.

When I took on the System Architect role, I encountered a completely new technology – the Internet of Things – that I knew nothing about. I also got to work with multidisciplinary teams – mechanical engineers, software developers, and embedded engineers. I had no clue how most of it worked.

What’s more, there was also a business development aspect to it. This whole project was about setting up a new business stream. They needed someone who could lead it from a technical perspective. The business requirements were unknown, and so the business model was unclear. It felt a bit like a startup within a corporate environment

In this project, I got to work with three different teams. I led one of them directly. The other two were interim teams of industry experts who worked with us as contractors. Formally, I didn’t get to give them commands. I just expected certain outputs.

I had to learn a different management style to work with people who knew way more than I did or knew everything about something I had no clue about. It involved avoiding getting entangled in technical discussions but keeping tabs on the output and results. I ensured they were satisfactory and aligned with the company’s direction.

My teammates were very knowledgeable about technology or engineering but perhaps didn’t always know the company’s context or the organization’s requirements. Our relationship was one of collaboration rather than a direct management style.

You weren’t very happy at this stage of your career. What did you do next?

At that time, I knew a lot about working as an engineer and managing a team of engineers, but I became interested in an even broader perspective.

I became interested in business development, sustainability, finance, HR, and other high-level aspects of the business. I wanted to know that my assumptions about how it should work were correct. However, I also wanted to apply the knowledge I gained from experience in a more structured way and learn from that, too.

I was faced with a decision. I wanted to take an MBA at Maastricht University. I could have decided to stay comfortable as an engineering manager, maintain the system, and do the MBA on the side using the limited time I had left. Or I could have accelerated my learning and focused on my MBA. I chose the latter.

Tell me more about your MBA. You completed it in 2021, and a year later, you joined Hiber. Not another year passed before you became Director of Engineering – the position you hold today. Was the MBA helpful in achieving this milestone?

Most definitely. If there are two types of people, experts and generalists, then an MBA is about learning how to be a generalist in your approach to collaborative work. That is key to being a leader, in my view.

The second skill set I learned in my MBA relates to personal development. It’s about answering questions such as: What’s in it for you? What makes you happy? Who are you? How did you end up here? And where do you want to go? Most people have a moment in their life when they sum up what they have achieved up to this point and wonder when to go next. That’s where an MBA can be super impactful when you’re open to it.

I learned to challenge my assumptions a lot. I’ve always considered myself a rational person. I looked for the most efficient way to achieve anything, and I thought this method was inherently superior to emotional thinking. That may come from my engineering education. Emotions are a bit of unexplored territory for many engineers, but the MBA forced me to take them more seriously, especially when working with people.

Emotional thinking has many applications in the business environment. It makes it easier to speak with people, to collaborate with them, and to manage them. As a leader, you also can’t ignore the emotions you have when you make an important decision. They are always there. You’ll be second-guessing yourself if you made the right choice or if you should take it back when it’s still not too late.

The Maastricht MBA also helped me identify a new area of interest: sustainability. I was never passionate about it before. When I allowed emotions into my decision-making, I felt I might use my skills and knowledge to contribute to a cause or purpose. Finding an opportunity to make a positive change now impacted my decision-making. Before that, I was all about being the most efficient.

From an engineer to a leader – skills (and where to find them)

We’re back in the present now. Let’s talk in-depth about some of the skills you have picked up along the way. There are also some questions that our readers would definitely want answered. Let’s see if we can do it.

Let’s start with the ability to influence others. Harvard Business Review says that this is what successful engineering leaders absolutely need. It seems like a no-brainer. But how to learn it? Or were you always a natural in it?

I think it’s a combination of who I’ve become along the way and what I learned during my MBA.

It is a bit arrogant to consider yourself the expert only because you are in a hierarchical leadership position. It’s quite likely that you have a lot of people around you who know more than you.

As a senior leader, you must be especially open and honest about what you don’t know. And let’s not forget that junior engineers or people coming from outside could bring in the latest knowledge, which is useful and great fun.

When you work with your team, you may take it upon yourself to impose goals, requirements, designs, or direction on everyone. If the team ends up in the wrong place afterward, people will think you don’t know what you’re doing. Then comes a negative spiral in which you hide behind your hierarchical leader position. You implicitly tell your teammates that you know the other person is right, but they should still listen to you. At this point, people will probably not care about the goal anymore.

As a leader, you are often expected to start a conversation. But don’t do it by imposing an opinion if it’s not your field of expertise. Instead, ask anyone in the group an open question about the best way forward. This creates a more natural conversation and an open atmosphere where people feel free to speak up.

And if they don’t speak up, you can again prove yourself as a leader. For example, If you notice a silent person in the room, you can speak to them directly and ask them for their opinion. Then, wait for the answer. Even the most introverted person has an opinion. Maybe you just need to wait a bit longer or ask the rest of the group to wait with you. There is a lot of unused potential from introverted people in loud and extroverted meetings.

Acting like this allows me to effectively lead teams that do things I don’t fully comprehend.

You also need to unlearn some things. Sometimes, managers have flaws that hold them back, like a need to micromanage, a habit of avoiding difficult conversations, or the opposite – being too direct. Have you ever had bad habits that needed to be unlearned? If so, how do you do it?

Everybody has bad habits. I’m not an exception.

Most of us have a natural tendency to think that we know better. You need to get rid of it as soon as possible. Even if you know the answer, consider other opinions before you speak up.

Another habit to unlearn is the tendency to romanticize leaders. When I was younger, I always thought of leadership based on what I saw in movies or read in history books. One person stood up, took the lead, ran forward, and everybody followed. Today, I don’t think that’s how it really happens. Perhaps this is how it is written down afterward. So let go of all your images of James Bonds, generals, politicians, kings, or queens.

Try a thought experience. You are a part of a new team. You don’t know anyone else on that team yet. Someone comes in and says: “Bart is now going to be the leader.” That creates an interesting dynamic right from the start. The person who is appointed as a leader feels automatically enlarged. At the same time, the rest of the group decides to listen to and follow Bart despite not knowing yet what his or anyone else’s capabilities are.

So, you should unlearn the habit of seeing yourself above the team. Instead, think of leaders as people who simply have a different role and set of responsibilities. They are the ones to facilitate things. They have a team of experts whom they want to help guide towards the best outcomes.

What about mentors who can help you learn all the necessary skills and eliminate bad habits? How to find a good one?

Having someone you look up to, like a manager or coach, already constitutes a mentorship situation, even if it is not said out loud.

You can also ask a colleague in your position: “Would you be open to learning together? We can share some reflections or exchange feedback in the coming months.” So, this could also take the form of peer coaching.

Overall, I would say that almost anyone can be a mentor, but some people are more open-minded and adept at expressing their opinions or feedback.

Let’s take two extreme examples.

One is a person you like working with, perhaps your best friend or partner. This person will likely be careful when giving you feedback and supporting you. Most people would go first to this person for feedback.

But it may be a good idea to reach out to a different kind of person for feedback – one that you don’t like or that is very different. It takes a lot of bravery to approach someone like that. But when you show some vulnerability and make your request, you’ll notice that you two will almost certainly agree. The animosity will fade away just enough to create an opportunity for a powerful learning experience.

As a more experienced leader today, you work with people who want to become leaders themselves. But it seems that not everyone is cut out for this. Did you ever tell someone they might be better off trying something else? What made them unfit?

First, we should ask what kind of leadership role it is. You could be in a company’s lower ranks and still act as a leader or expert in certain meetings.

There’s also hierarchical leadership, which is more about a position, career opportunities, and money. That could be more challenging. When someone plans to go that route openly, they may face some animosity. Having someone so goal-oriented and motivated on a team could feel threatening for your own role, but you should not be scared of such a person.

Try to be fearless. You would be an excellent leader if you could help this person evolve into someone who has more expertise or skills than you. How fantastic it would be to help someone grow even beyond your position. Isn’t that an incredible example of leadership?

However, you may also genuinely think a person is unsuitable for leadership roles. But you don’t have to tell them that directly. First, ask them why they want to be a leader. Try to help them and find out how they want to approach it. You’ll find out what is on their mind.

Then you can share your opinion. You have learned that this is perhaps a very challenging path. But if they still want to try, you would love to help. Tell them to keep you up-to-date about their progress and be supportive. Perhaps you’re mistaken, and this person is actually talented?

If you want to be a good mentor for your teammates, always let them be in the driver’s seat. They should experience what works and doesn’t themselves rather than hear it from you. It’s a bit like reading a book to someone. I already know how Cinderella ends. There’s no fun in this story anymore for me. But the child doesn’t know it. So, instead of looking for another book, let’s see what’s on the other page. Maybe it will turn out that it’s a different version of Cinderella, and you learn a thing or two.

Resources

I imagine failure to become a leader may also become a learning opportunity. Perhaps it will help one realize what one is really meant to do and what one is best suited for.

However, what learning resources would you recommend for those who stay on the leadership path?

During my MBA at Maastricht, I read a peculiar book about personal development, awareness, and group dynamics. It’s called Theory-U by Otto Scharmer.

It describes a certain way of behaving called the pre-sensing phase. Think of it as the sweet spot of collaboration, creativity, and future potential. Without going into details, it describes a method of achieving a most desirable state in which people are excited and motivated to exchange ideas and learn from each other with an open mind, heart, and will. “Leading from the future as it emerges” is just as relevant for technical brainstorming and teamwork as for any conversion you’ll ever have!

What’s next? Four actions for CTOs to take

Are you still interested in becoming a technical leader, even if instead of becoming a hero everyone looks up to, you will be no more and no less than a positive force that works in the background? Then, here’s your to-do list:

- Start conversations – share your opinions and respect the opinions of others. A good way to be opinionated and respectful is to ask a question.

- Facilitate progress – believe in your co-workers and subordinates. Don’t impose your will, and don’t do things for them. Help them learn by doing.

- Get honest feedback – find mentors in both people you like and dislike. The latter can be an especially useful source of sincere criticism.

- Find a balance – between a need to micromanage anything and a temptation to let go of everything. The higher you climb the managerial ladder, the more important it will become!

Do you want to find out more about Hiber?

Check out webinars, case studies, ebooks, whitepapers, and product kits to learn about HiberHilo’s capabilities, such as global coverage or near real-time messaging.